Life on the edge

Researching hydrothermal vent life in Iceland

This is a perfect day. The sea is completely flat, we have the Sun and the blue sky. The only thing is we need to be back before dark, but that will be in August.'

Erlendur, keeper of the vent.

'At this time of year, the Sun just doesn't go down in Iceland, which makes it fantastic for doing science', adds Dr Adrian Glover, a lead researcher from the Natural History Museum.

It's mid-summer and a team of researchers have travelled to Iceland to study a hydrothermal vent that sits just below the water of Eyjafjordur, a fjord on the north coast of Iceland.

Humpback whales breach in the bay in front of them and a thermal spring is the place to debrief the dramas of the day.

The vent they have come to study is called Strytan. What makes Strytan so special is that its chimney sits just 15 metres below the water's surface, making it relatively easy to dive to.

Many other hydrothermal vents form in the deep ocean and are hard to reach and study.

Hydrothermal vents are underwater chimneys made of rock and silt.

At a hydrothermal vent, hot water and chemicals escape from the sea floor into the surrounding ocean, creating a home for a vibrant cluster of animals.

The research team wants to know if and how the creatures living on vents have adapted to these steamy underwater places.

A laboratory at the edge of the world

The team have set up a temporary research lab in a disused herring factory. Their time will be split between this lab and a research vessel on the fjord.

The research team is made up of Dr Adrian Glover, Dr Maggie Georgieva and Dr Lupita Bribiesca-Contreras from the Natural History Museum, Dr Crispin Little from the University of Leeds and Dr Jon Copley from the University of Southampton.

They have brought microscopes, diving gear and cameras from the Museum, packed in three massive boxes and shipped from London.

In front of their lab, just a few hundred meters out to sea, the hydrothermal vent they have come to study lies bubbling under the ocean's surface.

Many billions of years ago, microbial life could well have originated at hydrothermal vents.

'One of the things that excites us about vents is really not just about this idea that it's the origin of life, but actually, that they've driven the evolution of animal life in our more recent oceans', says Adrian.

'These vents in Iceland are recent and shallow compared to deep water vents, we think they are around 11,000 years old. We want to see how quickly animals adapt to these unique environments,' says Maggie, who is studying these vents as part of her postdoctoral research at the Museum.

The keeper of the vent

Strytan was entirely unknown until it was discovered by Erlendur, a local diver.

He went looking for the vent in 1997. It wasn't on any maps, all he had was sonar evidence of the vent's existence.

Since his discovery, the vent has become a scientific and social treasure.

Erlendur brings researchers and divers here to see life in this unique place. He has been given the name 'keeper of the vent'.

Diving on a hydrothermal vent

Before diving, the team dropped a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) overboard. An ROV is a robot that has a camera and a mechanical arm that can be used to bring samples back to the surface. It's controlled by someone in the boat and is a great way to gather underwater information.

Crispin and Erlendur then dove down to the vent to collect samples. There are surface currents in the fjord, so they used a buoy and rope attached to the top of the vent to guide them down to the chimney.

It was demanding work. They needed to film, collect and record life on the vent but also make sure they didn't drift away in ocean currents or develop hypothermia in the 6°C water.

Having tasks made everything harder. When they found an interesting animal, Crispin would pick it up it, place it in a pot, screw the lid on and hand it to Erlendur. They also had to write down the number of each pot and the collection depth on an underwater clipboard, and use the temperature probe.

Their deepest dive on the vent chimney was 32 meters. Crispin says there is still a reasonable amount of light at this depth to have good visibility.

Life on Strytan

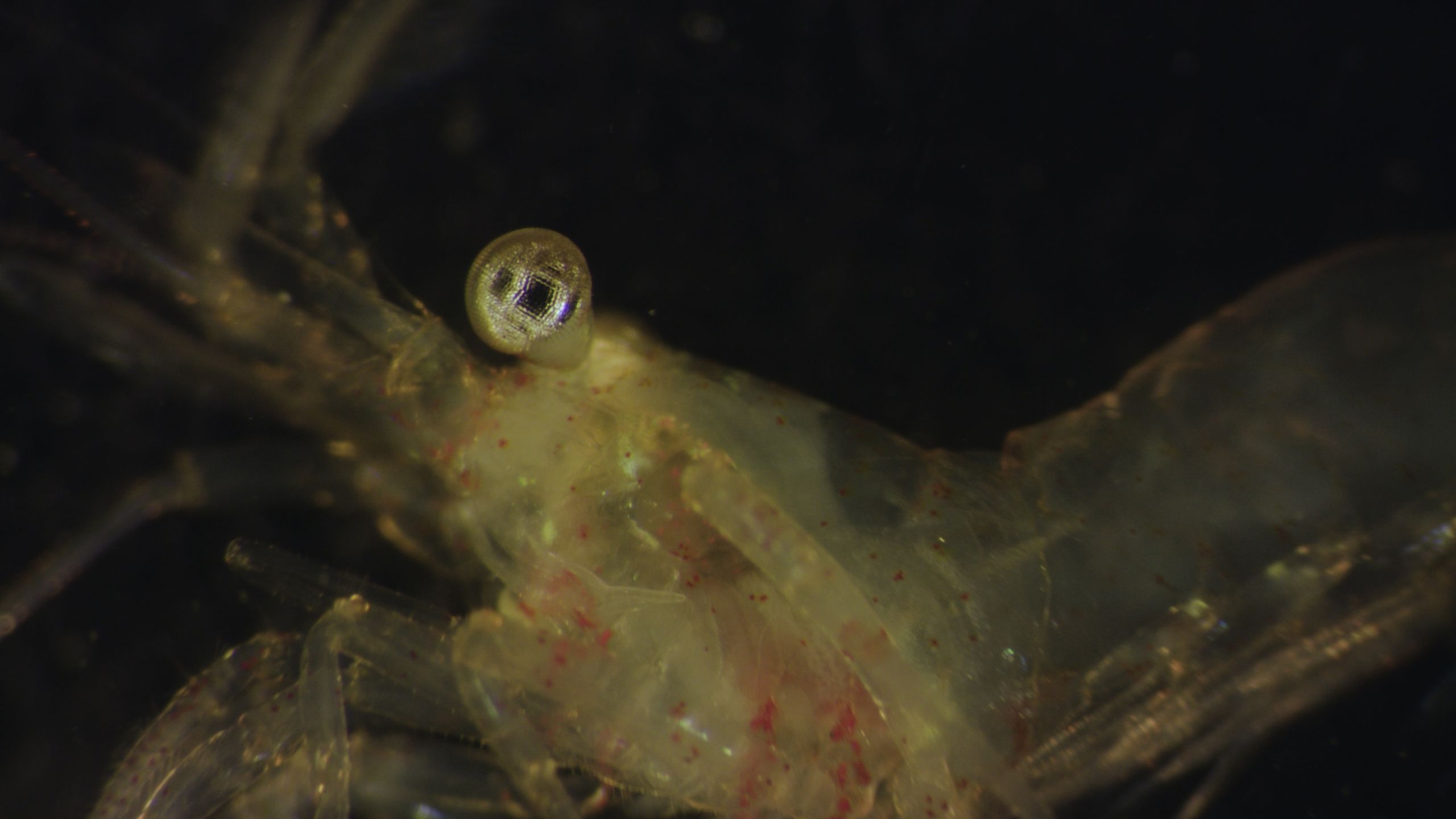

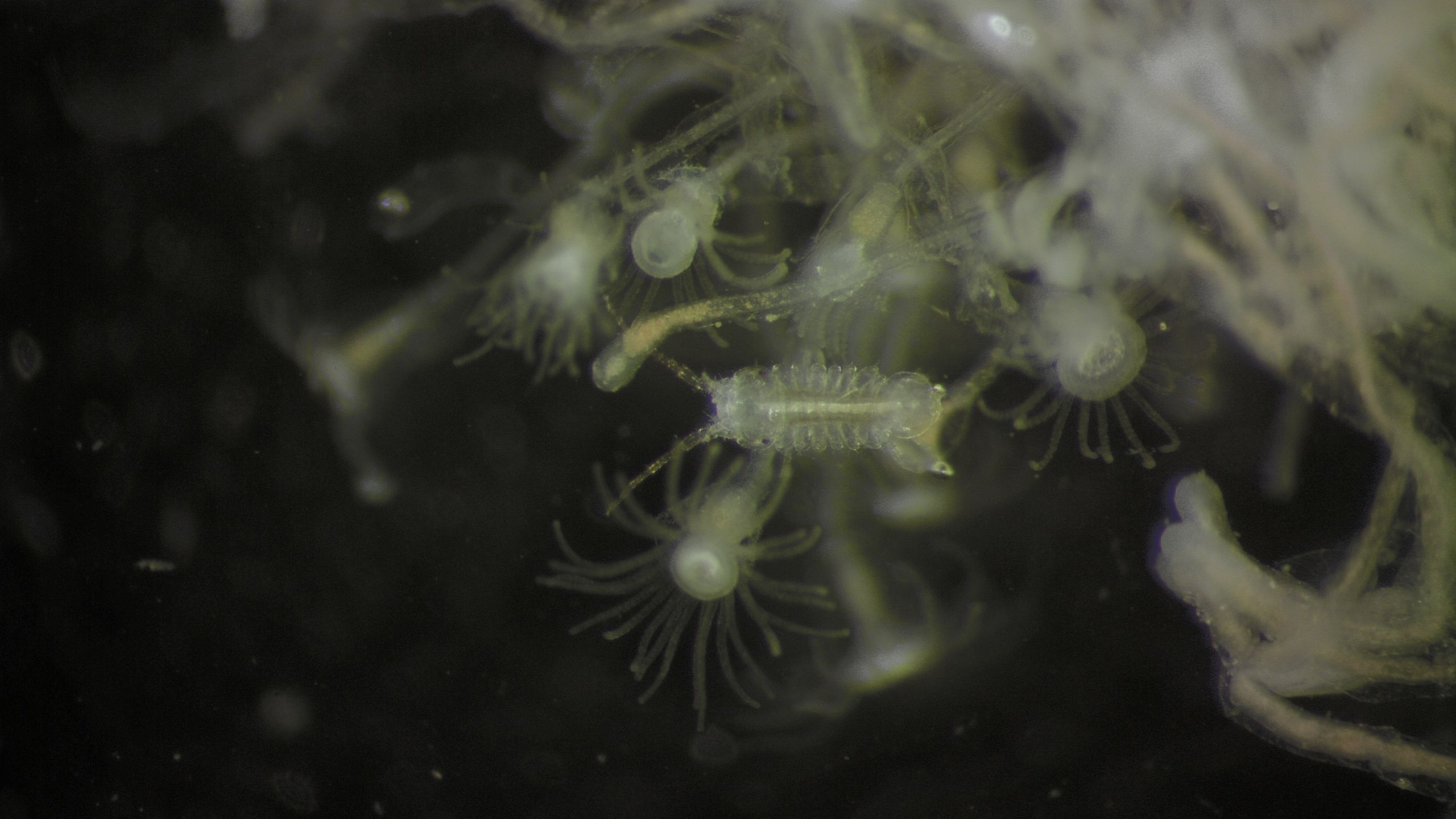

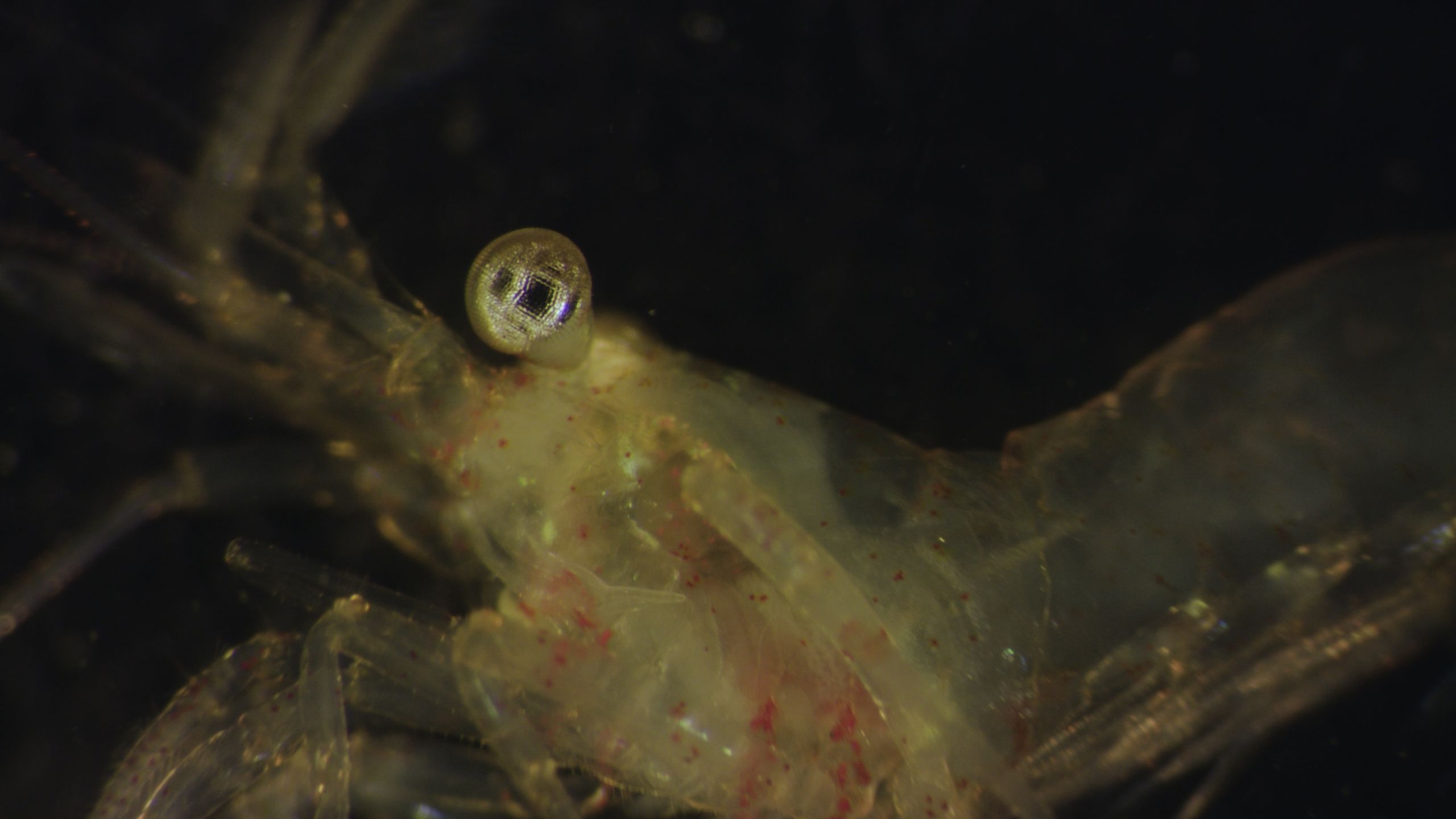

The research team collected around 220 animal samples to take back to the lab.

'When Crispin brought samples up there was so much tiny, unexpected life – it was like he was bringing up extra treats,' says Maggie.

'The idea was to immediately take a photograph of the animal and take tissue samples to see its genetic expression. You have to do this as soon as possible', says Lupita, who is also a postdoctoral researcher at the Museum.

'So now we've got samples from the diving, we'll take a small sub-sample from the specimen and preserve it inside a special solution, which makes sure its DNA doesn't degrade. And then we'll do further DNA analysis when we're back in London,' says Maggie.

Do animals living on hydrothermal vents have special adaptations?

Maggie hopes the animals they collected could give them an idea of long it takes for animals to adapt to the hotter, deeper vent environments.

'We want to explore whether the animals living on the Strytan vent chimney show particular adaptations to the hydrothermal vent, such as adaptations that allow them to handle the heat and chemicals and special associations with microbes,' says Maggie.

Animals need to harness the ability of microbes to live on deep-sea vents because microbes use chemicals in the heated water around the vent to make their energy.

'I'm looking at the microbiomes on some of the arthropods – there is some evidence that the animals that live on the vent are associated with a high number of bacteria', says Maggie.

Back in London, Maggie will continue to study the genetic code of microbes living on the animals collected on the vent.

Video and images by Geoff Marsh, words and production by Beth Askham, extra video editing by Lizzie Tilley

© The Trustees of the Natural History Museum, London

This research was funded by the Natural Environment Research Council

Learn more about hydrothermal vents