Mission Jurassic:

the big dino dig

Where dinosaurs once walked

It's been 145 million years since the last Jurassic dinosaurs roamed the planet.

Millennia have passed and today on the prairies of northern Wyoming, USA, it is hot and arid. At a glance, away from the isolated towns, the landscape is devoid of much save juniper, sagebrush and the occasional rattlesnake or black widow spider.

But evidence of a prehistoric world filled with lush greenery, dinosaurs and a variety of other extinct animals are just below the rocky surface.

In summer 2019, scientists from the Natural History Museum, London, set out for Wyoming to help reveal what has been hidden for millions of years.

The Stegosaurus skeleton on display in the Museum's Earth Hall was found near the small town of Shell in Wyoming, USA, close to the location of the Mission Jurassic dig site.

The Stegosaurus skeleton on display in the Museum's Earth Hall was found near the small town of Shell in Wyoming, USA, close to the location of the Mission Jurassic dig site.

The Jurassic Mile

A mission to study the Jurassic

Dinosaurs that lived during the Jurassic Period (around 201-145 million years ago) are arguably some of the world's best known. They include Diplodocus, Stegosaurus and Allosaurus - or, as Museum dinosaur researcher Dr Susannah Maidment puts it, 'all of the ones you knew when you were seven'.

But there is still plenty about these widely recognised animals and the world they lived in that we don't fully understand.

The first team from the Museum to arrive in Wyoming in 2019, led by Prof Paul Barrett, marked crossing the state border with a photo. (L-R) Simon Wills, Prof Barrett, Emma Bernard, Mike Smith, Dr David Ward and Tom Raven.

The first team from the Museum to arrive in Wyoming in 2019, led by Prof Paul Barrett, marked crossing the state border with a photo. (L-R) Simon Wills, Prof Barrett, Emma Bernard, Mike Smith, Dr David Ward and Tom Raven.

Mission Jurassic is a project led by the Children's Museum of Indianapolis, which aims not only to dig up dinosaur fossils for display, but also to learn as much as possible about what western North America was like 150 million years ago.

Two teams from the Natural History Museum joined the project in 2019 to help explore the Jurassic Mile - a square mile in northern Wyoming - bringing along experts in fossil preparation, microvertebrates, palaeobotany, fossil fish and marine invertebrates. The teams were led by dinosaur experts Dr Maidment and Prof Paul Barrett.

After two weeks on site, a second group from the Museum, led by Dr Susannah Maidment, took over from Prof Barrett and his team. (L-R) João Leite, Joe Bonsor, Dr Tim Ewin, Dr Maidment, Mark Graham and Dr Paul Kenrick.

After two weeks on site, a second group from the Museum, led by Dr Susannah Maidment, took over from Prof Barrett and his team. (L-R) João Leite, Joe Bonsor, Dr Tim Ewin, Dr Maidment, Mark Graham and Dr Paul Kenrick.

Prof Barrett says, 'All of the Mission Jurassic partners brought with them people who are either specialists in different scientific areas or have expertise in doing these kinds of excavations.

'By pooling that expertise we had a fantastically strong team.'

The Morrison and Sundance formations

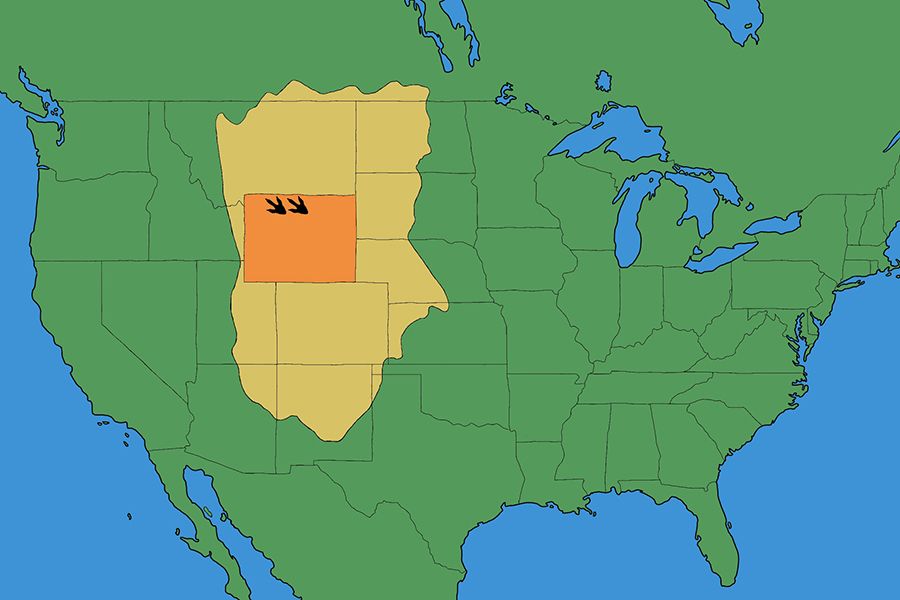

From approximately 160-157 million years ago, a shallow sea known as the Sundance Sea covered much of western North America. It was connected to the ocean by a narrow channel that stretched north for over a thousand miles.

As this sea withdrew, it was replaced by rivers and floodplains which deposited sediments and formed the rocks known as the Morrison Formation. Today only a small amount of this approximately 1.5-million-square-kilometre formation is accessible for palaeontologists to explore.

The Morrison Formation (yellow) stretches across roughly 1.5 million square kilometres of North America. The two dinosaur footprints on the map represent the approximate location of the Jurassic Mile in Wyoming (orange).

The Morrison Formation (yellow) stretches across roughly 1.5 million square kilometres of North America. The two dinosaur footprints on the map represent the approximate location of the Jurassic Mile in Wyoming (orange).

Dr Maidment says, 'During the Late Jurassic Period, about 150 million years ago, this area of Wyoming was a broad, shallow plain inhabited by dinosaurs like Stegosaurus, Diplodocus and Allosaurus. There were forests and plants - it would have been quite a green landscape.'

On the Jurassic Mile, evidence of these prehistoric reptiles is scattered across the landscape, with fossilised bones naturally weathering out of rocks and tumbling down the hillsides almost everywhere you look, and even more being slowly dug out of two quarries.

The Jurassic Mile is exceptionally rich in dinosaur fossils and the teams found lots of evidence of bones across the site

The Jurassic Mile is exceptionally rich in dinosaur fossils and the teams found lots of evidence of bones across the site

As well as the dinosaur-bearing Morrison Formation rocks, a large swathe of rocks laid down by the earlier sea are also exposed.

Some of the rocks of the Sundance Formation were deposited within a calm lagoon in exceptionally thin layers called paper shales. Palaeontologists can gently tease the layered rocks apart by hand or with tools to find plants and ancient animals, such as small fish and insects, fossilised between them.

Fossil fish curator Emma Bernard says, 'The rock is very finely laminated. It's almost like the pages of a book.

'A lot of the fish we found are quite small compared to the dinosaur material we see in the Morrison Formation, and they are very fragile. So we had to be really careful when we were excavating.'

The team also found abundances of belemnites, Gryphaea and oysters at different layers within the Sundance Formation, providing evidence of different marine environments.

A fossil fish found between layers of paper thin rock in the Sundance Formation

A fossil fish found between layers of paper thin rock in the Sundance Formation

Fossil invertebrates curator Dr Tim Ewin explains, 'Oysters are strange animals that can live in parts of the sea that other animals find difficult, whether because of the salinity, temperature or even the roughness of the water. As they are one of the few organisms capable of tolerating extreme environments and grow quite quickly, oysters can dominate an area. You can end up with very thick beds of oysters.

'If you see a profusion of oysters, it tells you that there is something unusual about the environment.'

The accumulations of different fossils found throughout the Sundance Formation, on the Jurassic Mile and elsewhere, provide evidence that sea levels and conditions changed considerably over time.

In one layer of the Sundance Formation, the team came across thousands of Gryphaea carpeting a hillside. These now-extinct animals are also known as devil's toenails.

In one layer of the Sundance Formation, the team came across thousands of Gryphaea carpeting a hillside. These now-extinct animals are also known as devil's toenails.

Dinosaur hunters

Searching the site

Dinosaur hunting can be quite low-tech. Palaeontologists can spend hours walking through a site and staring at the ground, searching for clues that a dinosaur might be hidden in the rocks below.

'Prospecting an area is key to finding new dinosaur material. We don't just go outside and find beautiful skeletons lying on the surface. It takes a bit of practice,' says Prof Barrett.

Dr Ewin searches for evidence of prehistoric life in the Sundance Formation

Dr Ewin searches for evidence of prehistoric life in the Sundance Formation

Bernard explains, 'Sometimes it can be tough to tell a rock from a fossil, and you have to really get your eye in. But one of the best ways to tell is to try and find anything black and shiny in the rock - that can often be a good indication of a tooth or scale.'

Although the Museum's experts are seasoned professionals, finding a fossil in the field is still an exciting experience.

But there are more than just dinosaurs in the Morrison Formation. Finding fossilised plants could help scientists to understand more about Jurassic ecosystems.

Palaeobotanist Dr Paul Kenrick explains, 'One of the really nice things about the Jurassic Mile is that you've got the bones of dinosaurs together with the plants. That really gives us the context of where these animals lived.

'Fossil plants are very common in the rock record. You commonly get leaves and fossilised wood. But one of the most common you can't actually see in the field - these are pollen grains and spores, which you have to take back to the lab and dissolve the rock.'

Dr Susie Maidment, Joe Bonsor and Dr Paul Kenrick examine a large piece of bone they found while prospecting the Jurassic Mile

Dr Susie Maidment, Joe Bonsor and Dr Paul Kenrick examine a large piece of bone they found while prospecting the Jurassic Mile

Plant life in Morrison time would have been much more productive than what is found in the semi-desert conditions of Wyoming today. There would have been predominantly tall conifers with an understory of ferns and small shrubs, as grass and flowering plants hadn't evolved 150 million years ago.

Sauropod dinosaurs like Diplodocus and Brachiosaurus were huge animals. Understanding the vegetation these herbivores would have relied on may help scientists to answer key questions, such as how these reptiles were able to grow to their colossal sizes.

Although palaeontologists know that the rocks of the Jurassic Mile are around 150 million years old, determining a more specific age is challenging - but that's exactly what Dr Maidment intends to do.

In marine sediments, scientists can use fossilised microscopic organisms to correlate rocks from one place to another, sometimes accurately determining their age. But because the Morrison sediments were laid down on land, this approach won't work.

'The only way we can date is to look for ash layers in the rocks, get minerals out of those and use radioisotopic dating. But that's also difficult because there's not very much ash here,' explains Dr Maidment.

Dr Maidment uses a hand lens to get an up-close look at a rock sample from the bottom of the Morrison Formation

Dr Maidment uses a hand lens to get an up-close look at a rock sample from the bottom of the Morrison Formation

Instead she and PhD student Joe Bonsor have logged the style of sediments to help compare the terrestrial rocks to those in other areas.

Bonsor says, 'We want to work out the geological history of the area. We want to know what the environment was like when the dinosaurs lived all those millions of years ago.

'To do that we have to measure the layers of rock, the grain size, any fossils, different sedimentary structures like ripples, which will give us an idea of the environment. We then piece all of that together and that feeds into the wider picture'.

Click and drag the 360° video below to go on a fossil hunting adventure with Dr Maidment and her team.

Tools of the trade

The Jurassic Mile has been explored by the Children's Museum in previous years. When Prof Barrett and his crew arrived in Wyoming in 2019, their first job was to begin clearing the site, which had spent the winter buried under a protective layer of rocks.

Prof Barrett says, 'We got into the quarries and started shifting rock and sweeping down the surfaces so that we could see what was going on.'

More exacavation in the lower sauropod quarry with a couple new bones emerging slowly from the quarry wall #MissionJurassic #WeDigDinos #NHMdino pic.twitter.com/keKN17zOQA

— NHMdinolab (@NHMdinolab) June 21, 2019

Once they had reached the bone bed, they slowed down and began to painstakingly reveal ancient animals millimetre by millimetre - a job Dr Maidment and her crew continued when they arrived on site two weeks later.

Mark Graham is the Natural History Museum's senior fossil preparator. His day-to-day role involves working with the fossils that palaeontologists bring back from expeditions. But on Mission Jurassic, he got to dig up the bones himself.

A large sauropod claw uncovered during the excavation of the Jurassic Mile

A large sauropod claw uncovered during the excavation of the Jurassic Mile

He says, 'It was fantastic on the first day to uncover a scapula of one of these gigantic dinosaurs, and later to find a large claw bone.

'Normally when I'm at the Museum, I'm used to opening field jackets, taking fossils out and making sure they're repaired if necessary. So exposing and stabilising them in the quarry is a slight role reversal for me.'

Finding large dinosaur bones isn't easy, but it's nothing compared to uncovering those of smaller animals, such as amphibians and mammals, which lived alongside them.

Finding microvertebrates is an important part of understanding what the environment would have been like in a particular area millions of years ago. A vertebrate is anything with a backbone. Microvertebrates are the parts of vertebrate animals, such as teeth or small bones, that have to be identified using a microscope.

It can be difficult to tell whether you're looking at a habitat the dinosaurs lived in, such as a coastal plain or forest, or where carcasses were washed to after death. But by finding other fossils around the dinosaur bones, you might get a better idea.

This is where Dr David Ward comes in.

Microvertebrate sieving machine aka 'Hank' is all set up and good to go (after several visits to the hardware store).@David_JWard @Simon_D_Wills #MissionJurassic #wedigdinos #wedigfish pic.twitter.com/8BkTlUCNnP

— NHM Fossil Fish (@NHM_FossilFish) June 23, 2019

He says, 'My initial interest is the evolution of sharks, but in order to collect sharks, I have to do a lot of sieving. So I developed an automated sieving machine that gently removes whatever is in the sediment without causing damage.'

Led by Dr Ward, the Mission Jurassic team constructed Hank, a field-based machine to speed up the microvertebrate sieving process.

Hank mimics the natural weathering process. It creates an artificial rainstorm with lawn sprinklers that spray water onto sediment samples to wash away clay and reveal tiny fossils.

A new experience

An opportunity to experience a real dinosaur dig is rare. For many, getting involved would be a dream come true.

Lead scientist Prof Phil Manning of the University of Manchester and the Children's Museum of Indianapolis says, 'I would have sawn off limbs to have this kind of experience as a student.'

Of the few students invited to join the dig, he says, 'I think it will have immeasurable positive outcomes in their careers, having taken part in an excavation like this.'

PhD student João Leite (left) aimed to learn all he could about palaeontological fieldwork from his time on the expedition in Wyoming

PhD student João Leite (left) aimed to learn all he could about palaeontological fieldwork from his time on the expedition in Wyoming

For three of the Natural History Museum's PhD students - Joe Bonsor, João Leite and Tom Raven - Mission Jurassic was their first experience of palaeontological fieldwork and, for some, the dig couldn't have started any better.

'I found a bone on my first day. We think it was a small piece of rib or part of a backbone,' explains Bonsor.

'Finding my first dinosaur bone was one of my main goals going out on the dig, and it was incredible. I was able to excavate the whole thing, wrap it in plaster and package it up safely.'

PhD student Joe Bonsor found a dinosaur bone on his first day digging on the Jurassic Mile

PhD student Joe Bonsor found a dinosaur bone on his first day digging on the Jurassic Mile

Leite says, 'It was a really cool experience and I tried to learn as much as I could. I was digging, prospecting and jacketing bones - all the sorts of things you can imagine happen on a dinosaur dig.

'I think one of the best bits was jacketing - just getting your hands covered in plaster, and protecting the bones and the surrounding rocks so they can be safely transported.'

The PhD students have each taken part in non-palaeontological fieldwork previously, but Mission Jurassic offered up some brand-new experiences.

'A big part of Mission Jurassic for me was to learn field techniques and become a bona fide palaeontologist,' explains Raven.

'It was definitely the largest expedition I've been part of. We had three international groups joining together with people with different expertise and specialities. Having that kind of collaboration is really great.

'I've never been involved in anything quite like it before. I had no idea what to expect.'

This month, students @JoaoVascoLeite @travenn @palaeojoe and @Simon_D_Wills have been in Wyoming with @NHM_London @TCMIndy and @UoM_EES looking for dinosaurs as part of #MissionJurassic - check out the hashtag for more info! #NHMdino #phdlife pic.twitter.com/OBwhNTViu4

— NHM_Students (@NHM_Students) June 23, 2019

Working in the wild

A deluge or two

The conditions on the Jurassic Mile were challenging at times and both teams faced delays due to regular downpours.

Dr Ewin says, 'If you don't evacuate the site immediately when it rains, the roads can become very treacherous and very muddy - much more so than I'd appreciated.'

Large weather systems passed over the site regularly throughout the Museum's time in Wyoming

Large weather systems passed over the site regularly throughout the Museum's time in Wyoming

The teams kept an eye on radars and forecasts, and when lightning strikes or getting stuck in mud weren't a risk, conditions on site were generally good. But temperatures were sometimes blistering, particularly in the Sundance Formation, where the rocks acted as a Sun trap.

Even when geared up with Sun cream, hats and plenty of water, exploration could be tough and the intense heat even cut short excavations of an Ophthalmosaurus, a type of marine reptile.

Dr Susie Maidment works in the intense heat of the Sundance Formation

Dr Susie Maidment works in the intense heat of the Sundance Formation

The weather wasn't the only safety concern. Although at a glance there was little life in the arid prairies, hidden among the abundant sage brush and prickly pears were a number of animals that kept the team on their toes.

Prof Barrett says, 'We had to keep an eye out for rattlesnakes and even for things like bears, bobcats and mountain lions. We didn't see any of them, but in the holes we were digging we did find scorpions and various types of spider, some of which are quite dangerous.'

Although there was a regular risk of accidentally stepping on an ant's nest or other more dangerous creatures, the area is also home to some far friendlier animals including rabbits and pronghorn deer. Dr Maidment explains, 'We saw some cute stuff, like prairie dogs which didn't get out of the way of the trucks, so we'd have to get out and chase them out of the road.'

Horned toads, which are a type of lizard, made several appearances on site during the dig season. They were one of the more friendly animals the team kept a lookout for.

Horned toads, which are a type of lizard, made several appearances on site during the dig season. They were one of the more friendly animals the team kept a lookout for.

Mission Jurassic

International collaboration

Mission Jurassic is led by The Children's Museum of Indianapolis in partnership with The Natural History Museum, the University of Manchester and Naturalis Biodiversity Center.

The Children's Museum intends to dig out two sauropod dinosaurs from the Jurassic Mile for display in Indianapolis, but has also been working alongside other institutions with a variety of expertise to study what the Jurassic environment and its dinosaurs were like.

Dr Maidment says, 'The Jurassic Mile is one piece of a jigsaw puzzle that is going to help us understand what environments the dinosaurs were living in across western North America.'

The official Mission Jurassic logo

The official Mission Jurassic logo

'This is a very unusual excavation insofar that we're dealing with a big international team,' explains Prof Manning.

'One of the most amazing things about science is when you get teams working together you can often discover things that you can't as individuals. My hope for the end of this project is that we've had multiple teams working together, pushing back the boundaries of science, helping us understand areas that we've never thought to look to before.'

Credits

Produced by: Emily Osterloff

Videos: Lizzie Tilley and Duncan Gregory

Additional content: Alison Shean

NHM team one: Prof Paul Barrett, Emma Bernard, Dr David Ward, Mike Smith, Simon Wills and Tom Raven

NHM team two: Dr Susie Maidment, Dr Paul Kenrick, Dr Tim Ewin, Mark Graham, João Leite and Joe Bonsor

With thanks to The Children's Museum of Indianapolis, Prof Phil Manning, Dr Victoria Egerton and Dallas Evans

© The Trustees of the Natural History Museum, London